Archive for July, 2011

Venereal Disease Poster, circa 1920

From the Alberta Archives comes this poster counseling persons wishing to get married to first get tested for venereal diseases. The poster appears to be directed at men. Compare the poster in my earlier post which uses a woman’s image and counsels servicemen to avoid contracting venereal disease from pickups, “good time” girls and prostitutes.

Earliest Example of Public Funding for Science in Canada?

I came across this 1806 Upper Canada statute, titled An Act to Procure Certain Apparatus for the Promotion of Science while compiling a comprehensive list of all health-related legislation in pre-confederation Canadas. It is most likely the earliest evidence of formal legislature-approved use of public funds for promotion of scientific research. I say “most likely” because a prior grant may have been made through an appropriations statute (the so-called “supplies” statutes). There is no prior, similar grant by the Lower Canada Governor and Council. This goes against a pattern I have observed in relation to health-related legislative developments in Upper Canada vis-à-vis Lower Canada, in which statutes passed in Lower Canada are followed a few years later (usually between 1 and 3 years) by similar enactments in Upper Canada (this is the subject of an upcoming post).

The 1806 statute provides a grant of four hundred pounds for the purchase of instruments to aid in the teaching of natural philosophy, geography, astronomy and mathematics.

We Said “Woman”, not “Prostitute”

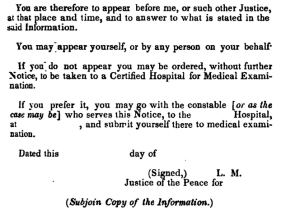

Between 1861 and 1867, the Upper Canada legislature enacted only one major piece of public health / health care legislation; this “gem” that would make a good case study of legislative attitudes towards women in the 19th century. The 1865 law, known as The Contagious Diseases Prevention Act, sought to prevent the spreading of contagious diseases (defined as “venereal diseases, including Gonorrhea”)—in designated places within the town or cities of Quebec, Montreal, Kingston, Toronto, Hamilton, London, Sorel, St. John’s and Chambly—by empowering certain law enforcement officials, medical practitioners and hospital authorities to identify, apprehend or facilitate the apprehension of, examine, detain and forcibly treat women suspected of being or found upon examination to be infected with contagious disease. The Act also makes it an offence to harbor a “common prostitute” who the host knows or has reasonable cause to believe has a contagious disease (not to be confused with the offence of keeping a bawdy or disorderly house). Other than through self-incrimination, it is not clear how the host was to ascertain this information about the prostitute, especially for asymptomatic diseases such as Gonorrhea (this WWII US Government poster borrowed from Wikipedia puts the matter in perspective).

(Of course, the same can be said for the “identify and apprehend” provisions aimed at women in general. Given the historical context, the reasons why the provisions did not apply to men, who were equally prone if not more likely to spread venereal diseases, are more apparent).

Interestingly, the word “prostitute” is only used in relation to the harboring offence; otherwise the Act generally applies to women, which means that proof that a woman is a prostitute is not required in enforcing the law. Thus, any woman suspected of having a venereal disease could be apprehended, forcibly examined, and “if it is ascertained that she has a contagious disease,” detained (up to a period of three months) and treated. Refusal to submit to examination or treatment was punishable upon summary conviction by imprisonment for up to one month for a first offence, and for up to two months for subsequent offences. Another interesting provision provides that proceedings under the Act were not to be carried out in open court, except with the consent of the woman being prosecuted.