Sir James Whitney Disagrees with the Anti-Vaccination League

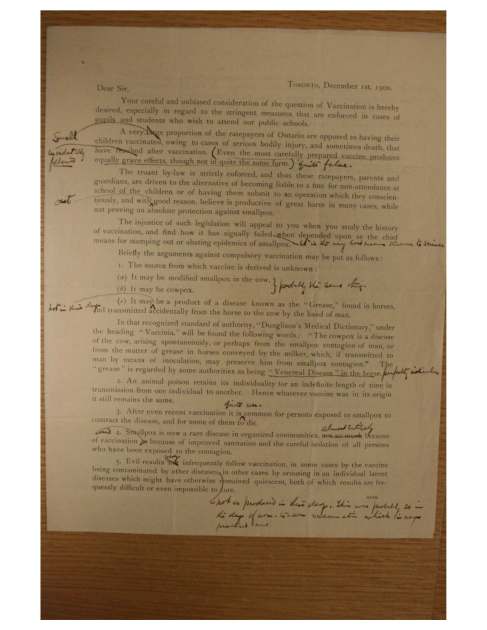

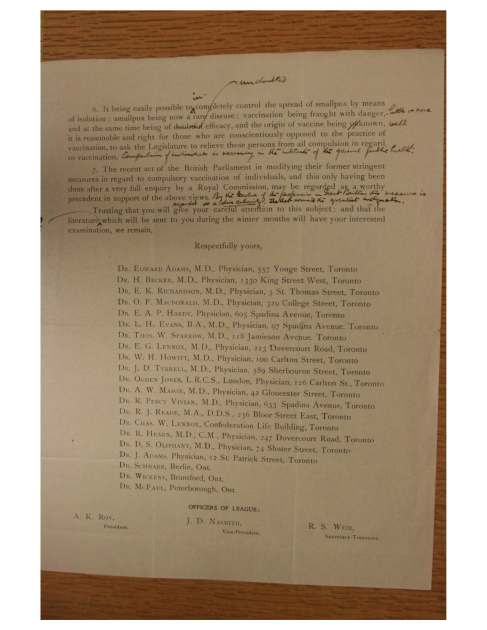

On Dec, 1, 1900, several medical doctors, mainly from Toronto, sent a letter to Sir James Whitney, the 6th Premier of Ontario and conservative MLA representing Dundas at the time, in which they laid out several arguments against compulsory smallpox vaccination laws aimed at preventing unvaccinated students from attending school (see photo below for full text of letter). The letter is interesting for a number of reasons. First, it is signed by members of the medical profession, which suggests, contrary to claims that anti-vaccinationism was a fringe movement among illiterate and misguided zealots, that there were anti-vaccinationists within the ranks of the profession at that time. Second, while it is not clear from the letter whether the doctors were acting as a formal group or association, signatories to the letter include three non-doctors identified as “Officers of League.” This suggests that the doctors were members of or that the letter came from the Anti-Vaccination League of Canada. Lastly (this is perhaps the most interesting point), the letter shows Sir Whitney’s apparent disagreement with the contents and arguments, in the form of pen-marked annotations correcting what he felt were false statements in the letter.

Source: Library and Archives Canada

Nineteenth Century Physicians, the Rhetoric of “Science” and the Professionalization of Medicine

I just finished reading SED Shortt’s brilliant review essay on the relationship between nineteenth century medicine and science, and more specifically, about how the medical profession employed the rhetoric of science to fulfill professional aspirations in advance of any real evidence of efficacy or therapeutic benefit. I have too many good things to say about this piece, and will recommend it as a must read for anyone interested in how language and “agenda framing” can be used to advance sectarian interests in the context of medicine, biomedical innovation and public health. A few choice excerpts:

On the relationship between medicine and science in the 19th century: “It would appear from…recent historiography, then, that science made little impact on medicine until the end of the nineteenth century.” (p. 58)

On prevailing historical and revisionist accounts of the link between science and medical professionalization: “Science is construed as a linear series of truths, each in turn awaiting inevitable recognition by a succession of astute investigators. In retrospect, a particular theory or innovation becomes “scientific” only when it is demonstrably a step on the path towards what is at present recognized as “true”. Contrary opinions or viewpoints that eventually withered, regardless of their contemporary reception, are rejected as “pseudo-science” and their adherents scrutinized to explain either deceit or gullibility. Only recently have historians of medicine indicated that they are willing to transcend this paradigm and accept the fact that each age has a unique body of knowledge considered scientific.” (p. 59)

And finally, on the co-option of scientific language to advance professional interests in advance of evidence of efficacy or therapeutic benefit: “Sub-groups within [medical practice] employed the rhetoric of science, often at the expense of colleagues, in their individual efforts to secure status and recognition. After the Civil War, for example, young neurologists attacked established alienists for their failure to rid nosology of antiquated terms such as “moral insanity” in light of developments in cerebral localization, cellular pathology, or hereditarian theory. That these new currents of thought made no significant contribution to institutional psychiatry was of less importance than the scientific terms in which they appeared to be couched. In a similar manner, armed with a vocabulary signifying scientific expertise, physicians in general hospitals displaced lay governors as the locus of decision-making… Yet the important shift in institutional power took place well before medicine could demonstrate the efficacy of its science.” (p 65)

My own work on legal developments surrounding legal adoption of smallpox vaccination in 19th century Canada suggests that medical professionals employed legal narratives and tried to enlist judicial intervention in this quest for professional status. Statutory rules rewarded the “faith” that doctors had created around the value of their own definition of science (aided by remedies such as vaccination that worked in spite of poor “scientific” understanding regarding its therapeutic value) by allowing them some control over health care and public health affairs, but never enough (at least until the end of the 19th century) to fully displace the orthodox system of health governance, managed by local /municipal officials, or the orthodox system of health care, characterized by a medical marketplace in which all sorts of practitioners provided health care services.

I will post some examples in a subsequent post.

Compulsory, But Not For Everyone

In 1861, the Province of Canada enacted the first statute to require compulsory vaccination in British North America. Similar to a statute passed by the British Parliament in 1853, the 1861 law mandated the vaccination of infants within three months of birth, and provided for free optional vaccination of others who could not afford the expense of vaccination. However, unlike the British law, the Canadian statute applied only in select cities: Quebec, Three-Rivers, St. Hyacinth, Montreal, Ottawa, Kingston, Toronto, Hamilton, London and Sherbrooke. I am trying to determine what these cities had in common, and welcome comments on this point. My guess is that given how unpopular coercive measures such as mandatory vaccination were at that time (the British law gave birth to the anti-vaccination movement, and measures like flagging of houses where smallpox residents resided were deemed “despotic” and “unnecessary” by pundits during this period), the legislature decided to test the measure in heavily populated areas where outbreaks were more likely to occur. The Province of Canada legislature received petitions to extend the provision of the Act to Sorel and Bonaventure, but an 1863 bill that would have made the law applicable throughout the Province never passed.

Disease and Drinking Cup Laws

Here is a fantastic example of how the fear of diseases provided impetus for much early public health regulation in Anglo-North America. In or around 1911, Alberta joined a number of US states in outlawing the “common drinking cup,” i.e. a cup customarily provided by public and private establishments for common public use. The obvious rationale for the ban was to prevent the transmission and spread of communicable diseases through cup-sharing. Bans were typically worded as follows:

“On or after [insert date], no cup, glass or other utensil used for drinking purposes ordinarily known as a ‘common drinking cup,’ in schools, hotels, boarding-houses, apartment houses, tenement buildings, theatres, public buildings and factories, or in connection with any public drinking fountain or water faucet in any street or park, shall be provided for the common public use.”

I find it interesting that the focus of the ban is on the cup rather than the practice itself (although the effect is the same). The wording suggests that regulators were open to measures seemingly less extreme than direct regulation of personal behaviour. After all, nothing in the provision prevents a party of cup-sharing enthusiasts from heading to the woods with a jerrycan of water and a goblet. It is also very interesting, as my colleague Sarah Hamill points out, that religious institutions, which typically engage in sacramental cup-sharing, are not included (at least explicitly) in the list of institutions subject to the ban (or, could they be classified under “public buildings”?). This 1898 monograph, which advocates abandoning germ-ridden sacrament/communion cups in favour of individual cups during communion service, indicates that the communion cup was a primary source of the mischief that the bans sought to prevent.

Curiously, the ban still exists in the Charter of the City of Portland.

Photo courtesy of the Canadian Public Health Association.

Connected Histories

I am a big digitization nerd, and I get really excited when I discover new digitization projects and resources, especially ones that make historical research a lot easier and faster. My latest discovery came through my Twitter feed this morning, and is called Connected Histories. The website aggregates eleven digital resources on British history between 1500 and 1900 (including British History Online, London Lives, The Proceedings of the Old Bailey Online) and allows the user to perform a single search of all the aggregated resources. This function is already hugely important and useful, but there’s more. Users can register for a free personal workspace that allows them to save searches and results, and to connect and share resources with others. What I really like about the connection function is that other users can only access the resources you share, and are not able to connect with you personally or even know anything about you other than your username. So, it’s basically a social network for resources without the baggage of personal connections. Brilliant. Connections can be associated with a course, which makes this a useful tool for organizing and distributing course materials. The website also provides comprehensive research guides arranged by topics, such as family history, crime and justice, local history, poverty and poor relief, etc., and detailed information about the included resources.

I took the search tool for a quick spin and I am quite impressed with the results interface. Results are categorized by document type, date and availability (free or subscription). Users can also access workspace functions from the results page, including saving or downloading of the searches or results, and Google +1 and Twitter bookmarks. My search results (for the word “vaccination”) also came up with an Old Bailey case that I had not encountered before, which I posted on my brand new HLBNA workspace.

I think this project represents the next step in digitization. Digital resources should be more than just a dump for scanned pages, but should provide users with tools for smart, comprehensive searching, saving, downloading, annotating and sharing, as well as helpful research guides.

Connected Histories is a not-for-profit service created by a partnership between the University of Hertfordshire, the Institute of Historical Research, University of London, and the University of Sheffield.

The Ordinary Antivaccinationist: Clowes v Edmonton School Board

The subject of today’s post is the first and only reported case on Alberta vaccination laws prior to 1920. The 1915 case is one of a number of cases I have compiled which deal with court challenges presumably initiated by ordinary citizens who were opposed to nineteenth and early twentieth century vaccination laws (similar court challenges were brought against mid-nineteenth century UK compulsory vaccination statutes, but on the basis that penalty provisions in the statutes violated the common law autrefois convict plea).

In the present case, plaintiff Clowes challenged a provision in Alberta’s Public Health Regulations of 1911 (enacted pursuant to the 1910 Public Health Act) which stipulates that no person was to be admitted to a school without proof of successful vaccination or of insusceptibility to smallpox, the disease for which vaccination was indicated. The basis for the challenge was that the regulation was subordinate to and in conflict with the Truancy Act, another Alberta statute that mandated compulsory school attendance (one wonders why this conflict was not detected during due diligence prior to enacting the Regulations). Clowes, who I imagine was one of many ordinary citizens who were opposed to vaccination at that time (the case was not reported in the newspapers, and I haven’t been able to find any information about those involved in the case outside of what appears in the law reports), sought an order of mandamus from the Alberta Supreme Court to compel the admittance of his unvaccinated son, Robert Gordon Clowes, to school. The court reluctantly found in his favour.

In separate opinions, each of the five sitting justices found that although the regulations were justifiably intended for the prevention of infectious disease and protection of the public’s health, and was much less intrusive than the compulsory infantile vaccination laws that then existed in England, it was nonetheless irreconcilable with the Truancy Act and as such, could not be upheld. Upholding the regulation would amount to repealing the Act or rendering it ineffective. Chief Justice Harvey referenced but distinguished a Minnesota case, State v Zimmerman, where the court upheld an emergency regulation that was similarly in conflict with a state law compelling school attendance. In Zimmerman, the Supreme Court of Minnesota upheld the emergency regulation on the basis that it was enacted pursuant to a statute on the subject of the preservation of public health and prevention of the spread contagious diseases, and being thus a statute “intended and enforced solely for the public good”, must be taken to be “primary and superior” to a statute that protects the right to attend public school. Echoing a common public health refrain, the Zimmerman court declared that as regards the balance required to resolve the conflict between both statutes, “the welfare of the many is superior to that of the few.” However, Chief Justice Harvey distinguished Clowes from Zimmerman on grounds that the regulation in issue was a general one, and not an emergency regulation.

Venereal Disease Poster, circa 1920

From the Alberta Archives comes this poster counseling persons wishing to get married to first get tested for venereal diseases. The poster appears to be directed at men. Compare the poster in my earlier post which uses a woman’s image and counsels servicemen to avoid contracting venereal disease from pickups, “good time” girls and prostitutes.

Earliest Example of Public Funding for Science in Canada?

I came across this 1806 Upper Canada statute, titled An Act to Procure Certain Apparatus for the Promotion of Science while compiling a comprehensive list of all health-related legislation in pre-confederation Canadas. It is most likely the earliest evidence of formal legislature-approved use of public funds for promotion of scientific research. I say “most likely” because a prior grant may have been made through an appropriations statute (the so-called “supplies” statutes). There is no prior, similar grant by the Lower Canada Governor and Council. This goes against a pattern I have observed in relation to health-related legislative developments in Upper Canada vis-à-vis Lower Canada, in which statutes passed in Lower Canada are followed a few years later (usually between 1 and 3 years) by similar enactments in Upper Canada (this is the subject of an upcoming post).

The 1806 statute provides a grant of four hundred pounds for the purchase of instruments to aid in the teaching of natural philosophy, geography, astronomy and mathematics.

We Said “Woman”, not “Prostitute”

Between 1861 and 1867, the Upper Canada legislature enacted only one major piece of public health / health care legislation; this “gem” that would make a good case study of legislative attitudes towards women in the 19th century. The 1865 law, known as The Contagious Diseases Prevention Act, sought to prevent the spreading of contagious diseases (defined as “venereal diseases, including Gonorrhea”)—in designated places within the town or cities of Quebec, Montreal, Kingston, Toronto, Hamilton, London, Sorel, St. John’s and Chambly—by empowering certain law enforcement officials, medical practitioners and hospital authorities to identify, apprehend or facilitate the apprehension of, examine, detain and forcibly treat women suspected of being or found upon examination to be infected with contagious disease. The Act also makes it an offence to harbor a “common prostitute” who the host knows or has reasonable cause to believe has a contagious disease (not to be confused with the offence of keeping a bawdy or disorderly house). Other than through self-incrimination, it is not clear how the host was to ascertain this information about the prostitute, especially for asymptomatic diseases such as Gonorrhea (this WWII US Government poster borrowed from Wikipedia puts the matter in perspective).

(Of course, the same can be said for the “identify and apprehend” provisions aimed at women in general. Given the historical context, the reasons why the provisions did not apply to men, who were equally prone if not more likely to spread venereal diseases, are more apparent).

Interestingly, the word “prostitute” is only used in relation to the harboring offence; otherwise the Act generally applies to women, which means that proof that a woman is a prostitute is not required in enforcing the law. Thus, any woman suspected of having a venereal disease could be apprehended, forcibly examined, and “if it is ascertained that she has a contagious disease,” detained (up to a period of three months) and treated. Refusal to submit to examination or treatment was punishable upon summary conviction by imprisonment for up to one month for a first offence, and for up to two months for subsequent offences. Another interesting provision provides that proceedings under the Act were not to be carried out in open court, except with the consent of the woman being prosecuted.

Emigrant Running

Image is courtesy of Harper’s Weekly, 26 June 1858.

This post is not directly health-related; while reviewing quarantine laws enacted in the Province of Canada between 1841 and 1867, I came across this fascinating 1862 statute about “emigrant running” and thought I’d write about it today. Following some quick internet research, it turns out that emigrant runners were 19th century touts who preyed on and exploited emigrants at arrival ports in British North America and the United States of America. According to Harper’s Weekly, the runners were “scoundrels of the very lowest calibre [who] seized [the emigrant] and made him their own. If he had any money, they robbed him of it. If he had a pretty wife or daughter, they stole them too, if they could.” Here’s more insight from the New York Times:

“Three ships loaded with emigrants arrived up from Quarantine, and it was a busy time all round…several…gentlemen dressed themselves in emigrants’ clothes and tried to gain admittance under the pretense of having been landed in company with those just arrived. But the dodge did not work. Others pleaded earnestly to get in to see a father or a brother, a sister or other relative, who was among the passengers. But they were too well known to palm themselves off on that pretense…These runners have sucked the life-blood of emigrants for so long that they think they have a right to it.”

But it seems the “runners” were travel agents as well. This 1854 case reported in the New York Times is about two runners, one named Jacob Rhinehardt, agent of the “People’s Line” transportation company, and another named Michael Williams. Rhinehardt was arrested and charged with fraud for telling arriving emigrants that the tickets they purchased in London for inland travel within the US were worthless, apparently as a ruse to sell People’s Line tickets to them. Rhinehardt was also charged with assault and battery on a German emigrant (the “tout” element emerges here). Michael Williams was charged with assaulting an emigrant named Jacob Albright. Interestingly, the magistrate in Rhinehardt’s case found that his actions, though morally questionable, did not amount to fraud because New York law would not apply to a contract involving a purchase of inland travel tickets from a foreigner unless the parties to the contract (the foreign ticket seller and the emigrant purchaser) met in New York to reaffirm the transaction. So in effect, Rhinehardt was right. Sort of.

Regarding the thuggish actions of Williams and Rhinehardt, the New York Times notes that the affidavits and evidence in both cases “show very plainly the outrages and extortions to which friendless emigrants are subject, not only here but in the European ports from which they embark.”

The legitimate and illegitimate nature of the emigrant running business might explain why the Province of Canada legislature chose to regulate rather than ban the practice. The 1862 law makes it illegal to engage in emigrant running without a license. The Act describes emigrant running as the practice of soliciting emigrants or making recommendations to them—on behalf of transportation companies, lodging houses or tavern-keepers—“for any purpose connected with the preparations or arrangements of such emigrants” for passage to a final destination in the Province or the USA. This may in fact be the first attempt to regulate travel agency in Canada.

Happy Canada Day everyone!